The streets of Milan were littered with empty bullet shells and concrete rubble. Out of a desolate street came strolling an American soldier. He was chewing gum and carried a comic book in the back pocket of his military uniform. Sitting down next to an Italian boy amid the ruins of a Europe that was about to be rebuilt, he leafed through the rough, yellowy pages of his comic and started sharing with the boy the adventures of heroic figures like Dick Tracy, a big-chinned detective chasing bad guys in downtown Chicago, and Flash Gordon, a space traveler fighting all kinds of monstrous creatures on Mongo, the Planet of Doom. The boy was enchanted.

What strikes me about Umberto Eco’s 1995 essay “Ur-Fascism,” in which the Italian author and philosopher recounts his youth during the first days of freedom after World War II, is the way it reveals a link in the European imagination between the liberation from fascism and the arrival of U.S. popular culture — as if Flash Gordon himself zapped the fascists with his ray gun, freeing Europe from Hitler just like he freed the planet Mongo from evil emperor Ming the Merciless. Since that first generation of kids to be bred on pop culture imported from America, its stories and aesthetics have become deeply infused into postwar European identities — whether it’s through after-school cartoons, pop music, Marvel blockbusters, or pulp science-fiction; the modern European sense of freedom is a dream dreamt through mythological heroes from the American pantheon.

Living in a time when fascism is surfacing in the U.S., and when Trump’s threat to invade Greenland seems to steer the NATO bond between Europe and America toward a possible breaking point, I find it unclear how I should relate to those American fictions that have formed my cultural consciousness so decisively. I was around the same age Eco was when I first started obsessing over sci-fi, fantasy, and superheroes, and few stories captured my imagination more than Edgar Rice Burroughs’s book series about John Carter, an Earthling trapped on Mars. Re-reading Burroughs now, though, I’m starting to think that the seeds of the particular kind of fascist politics practiced by the Trump administration were already sown in certain strands of the mythos of U.S. pop culture. What if the playbook of ICE raids and imperialist foreign interventions has always been forecast in the aliens and spaceships of the sci-fi I was raised on?

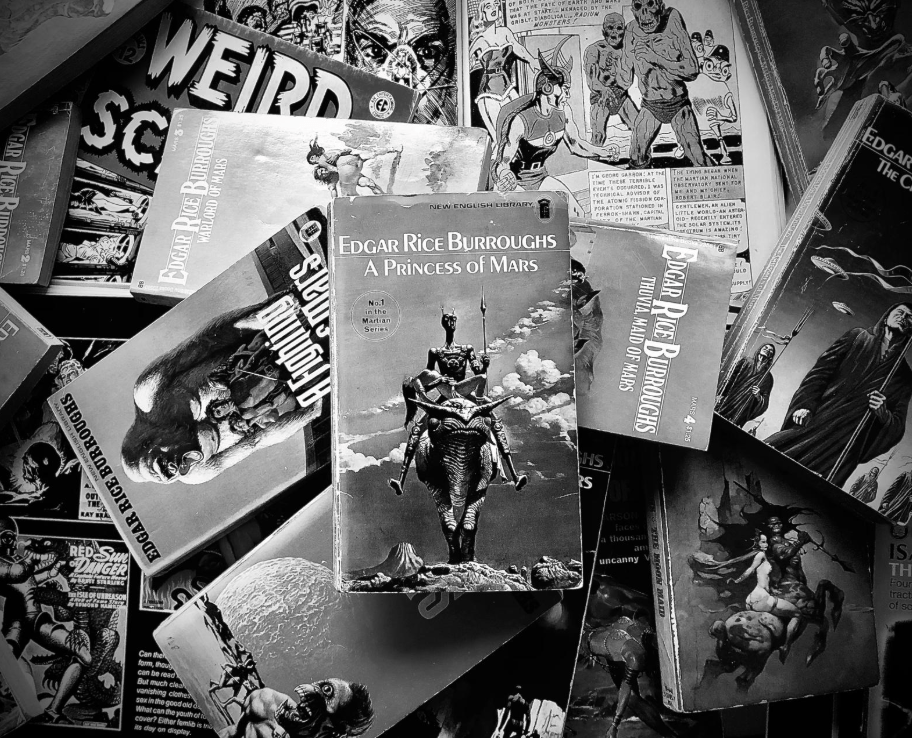

Around the time Nazi Germany put its first eugenic sterilization laws into effect, subjecting citizens who were thought to poison the genetic purity of the Aryan race to forced sterilization, Edgar Rice Burroughs was writing a staggering amount of fantasy books. Between 1912 and 1944, Burroughs produced more than sixty novels chronicling the adventures of figures like Tarzan of the Apes, John Carter of Mars, and Carson Napier of Venus among many others. All his works, though, follow the same basic formula: against his will, a (white, male) protagonist finds himself stranded in a strange world where he is confronted with a race of non-humans that need to be conquered. A prime example is John Carter, an ex-Confederate soldier who goes gold-mining in Arizona to rebuild the riches he lost during the Civil War, only to be chased by a band of Apaches and driven into a cave where a trance-like experience teleports him to Mars. The first book of the series, A Princess of Mars (1912), follows Carter as he quickly becomes warlord-king of the planet by rescuing Deja Thoris, princess of the noble and intelligent Red Martians, from the Tharks, a savage race of green, multi-limbed aliens with little capacity for empathy.

Burroughs’s depiction of Mars is in direct dialogue with American frontier myths, which nostalgically imagine the earliest chapters of U.S. history as courageous westward expansion turning the wild open into civilized settlements. The plot of A Princess of Mars could easily be read as a sci-fi rehash of Indian captivity narratives, a story-tradition that props up indigenous peoples of the Americas as satanic barbarians bent on destroying the colonial enterprise by capturing and torturing settlers. The drama of these myths lies in the fear of losing touch with civilization and becoming savage, while the redemption comes with the rescue of those captured (often, a role played by women). Burroughs’s Martian makeover of frontier mythology offers escape from what I’ll call conservative melancholy — or, the inability to fully accept the loss of a conservative social order. Strip away the sci-fi mystique and the alien-slaying, and John Carter is simply an ex-Confederate soldier struggling to find his footing in post-Civil War America: “at the close of the Civil War I found myself […] the captain of an army that no longer existed; the servant of a state which had vanished along with the hopes of the South.” Written half a century after the Civil War, the Mars books frame the victory of the more progressive North as a mournful defeat, perceiving the Confederate way of life, built on racial hierarchy and the legal institution of slavery, as being increasingly left behind with each slow and tense step toward racial desegregation. The red planet functioned as a mythic playground for Burroughs to role-play social relations that were no longer a reality as American cities were becoming more ethnically diverse and socially complex.

If John Carter had lived today (and weren’t fictional), he would have voted Trump, whose politics similarly have a knack for escapist narratives that respond to a perceived loss of American greatness. His administration displays its courage by endorsing such bizarre projects as Elon Musk colonizing Mars and Peter Thiel’s vision of “freedom cities” detached from the rules-based international order. Trump openly celebrates these undertakings for “reopening the frontier,” “reigniting the American imagination,” and reviving the “boldness” he claims Americans have lost since the nineteenth-century boom of industrialization and infrastructure created the sprawling metropolises that dominate the modern landscape. What makes this narrative escapist is that it imagines a version of American history that displaces its diversity; the explosive growth of urbanization in the post-Civil War era was made possible, not first and foremost by white entrepreneurship, but largely by immigrant labor — from Europe, yes, but also crucially from Latin America. Erasing certain bodies from history cuts them out of the way the future is imagined. This is made tragically clear in the ongoing ICE raids, which sterilize the nation by (mostly) targeting non-white immigrant communities in preparation for such sadistic projects as the “freedom cities.” The fascist component of this escapism, then, is the way it appeals to — what in MAGA ideology is perceived as — a loss of traditional cultural identity in order to exert violent state power over those not included in what is often arbitrarily deemed an American citizen.

The trick is to realize that these fascist views have a history in the U.S. that predates Trump. Just as in Nazi Germany and Japan under Hirohito, America in the early twentieth century saw much public debate on the validity of eugenics. This pseudo-scientific theory of race, which posits that the genetic composition of society can be engineered and improved, was a key trait of nineteen-thirties fascism, obsessed as it was with preserving racial purity and exterminating degenerate genes. Burroughs was among a sizable group of Americans who saw eugenic sterilization laws as a decent form of population control. In a non-fiction piece titled “I See A New Race” (written in 1935, mind you, two years after the Nazi party had implemented their own eugenics policies), Burroughs envisions a future utopia in which the human race would be cleansed of all forms of degeneracy — moral, intellectual, physical. He writes: “the sterilization of criminals, defectives and incompetents together with wide dissemination of birth control information and public instruction on eugenics resulted in a rapid rise in the standards of national intelligence after two generations.” This cruelly optimistic take on eugenics wasn’t unique at the time. As early as 1921, the U.S. Committee of Immigration and Naturalization advocated for eugenic profiling in an attempt to legitimize the enforced sterilization and deportation of immigrants.

What makes reading Burroughs’s article on eugenics difficult is that it is written in the same speculative voice found in much of his sci-fi. The opening passage of The Moon Maid (1923) similarly sketches out an imagined history of the twentieth century that ends “at last with the absolute domination of the Anglo-Saxon race over all other races of the World.” With the project of absolute racial subordination completed already in the prologue, the rest of the story follows its protagonist exploring Earth’s Moon. What he finds there can best be described as a eugenics parable: a once-great society has collapsed after education was made available to all alien species living on the Moon — most troublingly, to the Va-gas, a race of humanoid horse creatures Burroughs repeatedly compares to the “savage Indians of the western plains.” Whereas the green Martians from A Princess of Mars were an implicit metaphor for Native Americans, here the quiet part is said out loud. And the message is clear: keep the aliens out.

If you want to trace the lineage of fascist eugenics in American culture, the line you draw passes through Burroughs’s article and leads straight to Trump’s statement that “we’ve got a lot of bad genes in the country right now” when discussing the “murderers” crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. Strategies like bringing back the Alien Enemies Act (a dusty old law from 1798, recently invoked by the current administration to deport hundreds of Venezuelans to a prison camp in El Salvador) simply expose a latent fascism that has always lurked just underneath the surface. Repressed in the myths of the American unconscious, where it dreams of strange worlds and aliens and heroes in space, we find the same neurotic anxieties that have always fueled eugenic beliefs and the muscle-politics necessary to enforce them.

Scouring through different news channels and re-reading my collection of John Carter novels (yes, I have all eleven parts, no, I haven’t read them all yet), I can’t help but think back to those days of my childhood spent with eyes wide open on endless pages of these weird stories, the way they completely fired up my imagination, the way printed text took flight. And I can’t help but think back to Umberto Eco: how, as a small boy at the dawn of a new kind of world prophesied to be rid of fascist power-plays, the brightly colored panels of American comic book heroes must have stood out against the ash gray of a ruined city. Eco and I are bookends of a period in Western history that is coming to a close. How to read John Carter in the times to come? Must we burn Edgar Rice Burroughs?

Written by Victor Keyser

Leave a comment