When I had the opportunity to have a couple of sessions with two pop producers a few months back, a conversation we had made me notice a recurring pattern among producers and musicians without conservatory education. They described the conservatory as over-rated, failing to produce the best of the best musicians, and the students too arrogant and diva-like to work with. And I, awkwardly positioned between being empathetic to their complaints and my loyalty to my conservatory educational background, remember expressing a few points about the practical shorthands that the education lends you in navigating rehearsal communication, music theory and of course the playing itself, but acknowledged that these tools function best when ego is not the driving force. Perhaps they wanted to preserve the romantic notion of music as a purely affective form. Perhaps they were complaining for the right reasons, the societal distinction between high and low culture remaining stubbornly fundamental as to completely lapse. Although I am cautious not to validate their exhaustion, it seems too early to do so: there are too many new and impactful sub-forms of art consumption emerging to dismiss their capacity to reframe existing cultural divides, and too many artists emerging from art schools that resonate with the mass audiences of today.

A particular jam I went to two weeks prior turned out to be a blissful mistake that would later shape my thoughts on the conversation. Two sessions were both named Super-Sonic Jazz jam, and the one I went to was at the basement of Paradiso whilst I really should have been at the one in Skatecafe. Super-Sonic Jazz Skatecafe jams were legendary and my initial disappointment rose from the fact the Paradiso one resembled more of an extended, looser form of the festival held earlier that evening than a proper participatory jam. When I had entered, the place was packed and stuffy, the crowd extending as far as I could see from the back with my limited height. Although I could hear the music, the sound was physically barricaded and filtered by chatter of a crowd who seemingly weren’t too engaged. While I gazed absentmindedly, debating whether to make my way into the crowd, I had caught a glimpse of the face of the trombonist with his eyes wide, intensely staring ahead into the void, his eyeline just grazing above the crowd whilst blowing into his trombone. He’s stressed, I thought.

Stress visits performers in various ways especially when the whole essence of the music runs on immediate risks. This risky gamble for me, demonstrates a sense of Art for Art’s Sake, a gamble within a league of its own in seclusion from the external world. Pop music on the other hand, tends to be more managed and harboured to focus on the emotional resonance of the consumers. Pop is the representation of a momentous cultural sensibility of the present world and the consumers onboard with its conceptualizations. It wouldn’t be a surprise to hear that it is often much less difficult to find a conceptualization in pop music that intuitively resonates with a young person’s aesthetic judgment than within the classical canon that encapsulates a historically long-lasting aesthetic value. What is a surprise is how soon this too changes and the functions projected onto music fluctuates per individual. How rare is it for me to now encounter that same fundamentally transformative experience that I had watching a resonating pop concert at an age where taste drove how I defined myself? At least in the live context, I was moving onto something impersonal in which I could sit back and watch the participants’ negotiation of risks unfold as you would a high-stakes football game.

By the time I had moved quite close to the stage, having incrementally progressed each time someone moved to the back, it seemed everyone in this particular game was losing. They were playing a game of a certain contemporary jazz tune I had not heard of whilst the tuning of the trombone was off, the keyboardist wasn’t keeping the form and the rhythm section was not locking in. Overall it sounded like they didn’t really know the tune and many musicians would agree that risks cannot play out when the foundational structure is shaky. Fortunately for the second set, a replacement drummer swooped in whilst the saxophonist announced that they have no idea what he will play and left it at that, waiting for him to start. Then with a snare hit, the drummer began a 16th-note-based funk groove with a displaced backbeat, and I felt the room focus. After a couple of bars, the bass and keys percussively joined in on the rhythmic complexity to which the drummer smiled. The tune was “Actual Proof” by Herbie Hancock, the touchstone of jazz-funk fusion as well as being known for being rhythmically tricky for those playing. Soon enough when the keyboard solo started, the drums switched to an unprecedented super-imposition of a hard-hitting disco groove to which the bass quickly locked in with the kick-drum, pulsing the tune with a repeating short motif and the basement began to dance. The musicians became visibly much more at ease and when the saxophonist failed to execute a line during her solo, all the trombonist did was laugh as the room was already on their side.

Critical evaluations have emphasized the large negative reception Hancock received in the 70s on his jazz-funk transformation from jazz music critics who advocated purist ideas of high art and those who saw his commercial success as yet another example of exploitation of black people’s underground music for white people’s pleasure (Larson). Hancock denies intentionality in his music’s capitalist involvement in his interview with Wynton Marsalis in which he coolly comments, “Look I’d like to have a Rolls-Royce, but I’m not trying to set myself up to get a Rolls-Royce” (Marsalis 350). Cut to the 90s when the post-colonial concept of cultural multiplicity and hybridity was consolidated by Homi K. Bhabha, marking the perception of radical juxtaposition of cultures as authentic and sameness as mimicry that only causes imperial insecurities, completely changing the trajectory of how we think about cross-cultural production (Bhabha 74). Though with some transformations, the foundation of Bhabha’s idea persists today, and Super-Sonic Jazz Festival represents the growing number of platforms that aim to bring the proliferation of ‘boundary-pushing’ music to practice, focusing on hosting an attitude of “spontaneity and creativity” (“FAQ”) over a fixed genre of music.

Creatively enough, the musicians at the jam had incorporated two genres of music that both had commercial successes in the 70s, creating a reunion of the risen subculture of the time. What differentiated them now is that one was continuing to be implemented in today’s pop music whilst one had become fairly institutionalized as a progressive minor canon in conservatory education. Yet, in Paradiso’s basement, this differing degree of capitalist involvement ceased to exist and was flattened out with the focus put on their commonality and their alignment with the mission of Super-Sonic Jazz to celebrate cultural hybridity. It successfully and temporarily created a sense of seclusion from the external world in which despite the growing platforms for fusion music, continues to be marginalized from the mainstream in practice. The communal narrative I created watching the musicians’ on stage on the one hand, and the communal resonance I felt with the crowd on the other, made the experience ecstatically layered and immersive, allowing me to fully commit to even the growing stuffiness of the room.

What role, I wonder, do these concerts take on the collapse of high and low culture? Is it a significant reframing of the high/low divide if the already culturally saturated forms of each genre have combined to produce a more saturated whole? Sarah Thornton argues that contemporary culture is so finely divided that clear-cut oppositions between cultural forms have become increasingly blurred, with their lineages entangled, and noticing differences has become more like noticing distinctions (167). If the jam’s significance derives primarily from equalizing the current differing capitalist involvement of the two genres through a single platform, then it is less about the music’s inherent qualities and more about the contexts in which these genres are situated, contexts that allow contemporary social reflexivity and imagination to emerge for the current generation.

At this time, hierarchies of high and low culture continue to operate within broader social and institutional structures outside of individual cultural objects and episodic experiences. The coexistence of this high/low divide with the finer cultural distinctions described by Thornton, allows the two to function dialectically. Thus, when Thornton further argues that the fine cultural divides intensify young people’s pursuit of distinction for whom taste is crucial for self-identification (166), it follows that the high/low divide plays a role in processes of self-identification. Thinking back to the conversation I had with the two pop producers, who themselves were enrolled at a music institute at the time, I recall how they described encountering hostility and rejection when attempting to negotiate a collaboration with conservatory students. In hindsight, I wish I had responded differently. Navigating spaces in which cultures may appear similar on the surface, yet are structured by enduring pursuits of distinction, both small and large, presents its particular challenges. I am left wondering what might have emerged from that conversation had I acknowledged their experience rather than defended and justified the conservatory’s significance.

References:

Bhabha, Homi. K. The Location of Culture, Routledge, 1994.

“FAQ”, Super-Sonic Jazz, https://www.supersonicjazz.nl/faq.

Marsalis, Wynton & Herbie Hancock “Soul, Craft, and Cultural Hierarchy.” Keeping’Time: Readings In Jazz History, In Walser, Robert, Oxford University Press, 1999, New York, pp.339-351.

Larson, Jeremy D. “Head Hunters”, Pitchfork, April 5, 2020, https://pitchfork.com/reviews/albums/herbie-hancock-head-hunters/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

Thornton, Sarah. Club cultures music, media and subcultural capital, Polity Press, 1995, Cambridge, UK.

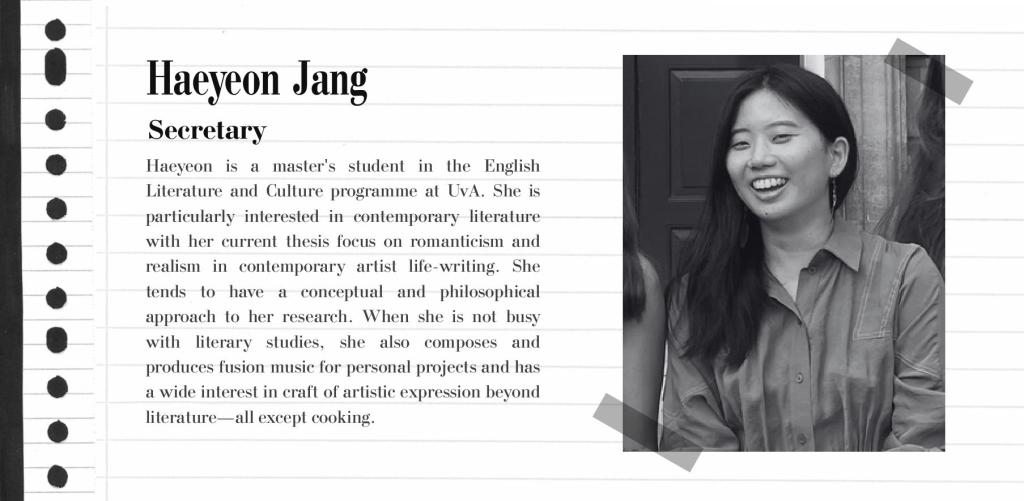

Written by Haeyeon Jang

Leave a comment