“Wear your heart on your skin in this life.”

~ Sylvia Plath

Tattoos are a controversial subject in my family. Ever since I could comprehend speech, my grandmother has been telling me that if I ever get a tattoo, she will take out the rolling pin, which my uncle is dearly familiar with. She told me that one of the most frightful moments of her life was when she went to visit him in the US and discovered a drawing etched onto his shoulder. Fortunately for him, she had not brought her weapon of tough love with her. She would shudder just recalling the memory. I don’t fully understand why she is filled with such disgust for the practice of tattooing, although it is an opinion that has undoubtedly been shaped by the traditional, timid communist environment she grew up in. Now her hatred has grown so strong that she winces whenever we pass by a stranger covered in tattoos. It’s a physical reaction, as if she’s allergic to the concept. Her gullible nature has also made her the victim of many tattoo inspired April Fool’s pranks. She scolds us that she’ll get a heart attack one day because of our antics. With my cousin’s recent stride into the tattooing world (still kept under wraps) and my own interest in perhaps one day joining her, I want to defend tattoos to prepare my poor grandma, and possibly prevent cardiac arrest. I feel as though I can somehow prove to her that tattooing is a legitimate, multilayered form of art, one that isn’t to be feared, but to be appreciated.

Definition and Arrival In the West

A good first step is a definition. Defining a concept clearly demystifies it and makes it more approachable, fosters understanding. The verb to tattoo was originally defined as “marking the skin with pigments” (Goldstein), when it was brought to the Western world by Captain James Cook and Joseph Banks, his resident botanist, in 1774 after traversing the Pacific islands. The concept of tattoos existed outside of tribal practices before this journey, but it was never given a term; instead the action was described, as was the case in the 1611 King James version of the Bible: “Ye shall not make any cuttings in your skin for the dead, nor print any marks upon you” (Leviticus 19:28; my emphasis). The term we use now was standardized through Captain Cook’s interactions with the Tahitian and Marquesan peoples, who used the words tatau and tatu, respectively. An interesting fact about these travels is that a few of the sailors (notably, Sydney Parkinson the resident artist, whose role was to document the trip visually) came back inked themselves, apparently inspired by the tradition and believing that the markings would serve as protection. They also jumpstarted the spread of sailor tattoos within European travelers. Now that I have already dipped our toes in the historical background of the art, I will sketch a brisk outline of tattooing conventions throughout history.

Brief Cultural History

There are many novels written on specific nations’ tattooing practices and countless archeological research papers, but my purpose here will be to underline the longevity and importance of the tradition. Every civilization has had some sort of tattooing custom according to Charles Darwin in his The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. Different materials, different purposes and different techniques are, and were used, but with a similar result – etching ink under the skin is a human urge. The earliest evidence of that urge comes from Ötzi the Iceman, a mummified man found in the Oxtal Alps, who sports 61 tattoos across his body, mostly on his legs. He was discovered in 1991 and his death is dated between 3350 and 3105 BC. What follows is a historical overview of cultural patterns in tattooing:

- Ancient Chinese and Ainu (from Northern Japan and Southeastern Russia) tattooing was done in order to protect oneself from evil forces.

- In the Polynesian and Samoan cultures, tattooing was performed by the father on the son, granting him ancestral protection and a mark of belonging to the family. They included natural motifs and showcased personal achievements and pride.

- In Ancient Egypt, marking of the skin was used as a cure to different ailments or as a therapeutic procedure during pregnancy. Tattoos were a symbol of fertility and women’s health, and spiritual, as well as physical guidance (through a sort of ancient acupuncture). The most famous Egyptian mummy found to have markings was Amunet, the priestess of Hathor, goddess of fertility and childbirth. Her tattoos are theorized to have been placed to alleviate chronic pelvic peritonitis (inflamed abdomen tissue).

- In Chin (from Burma, or modern day Myanmar) culture, facial tattoos were a beauty standard for women. They also signified coming of age and their designs would reveal the wearer’s social status.

- Aboriginal Australians’ tattoos symbolize the interconnectivity between the human, physical and sacred realms. They call the period of creation of the world the Dreamtime and the artwork they inscribe on their skin is connected to that belief. They also believe that everything “living”, or organic (animals, rivers, trees), is their ancestors. Another tattooing culture that was closely linked to its land was that of the Celts. They used the traditional Woad plant to produce blue ink, which they etched under their skin. The literal aspect of the sacred material becoming a part of them, connected them to their environment.

- Indigenous groups in the Philippines before the Spanish conquest saw the marking of the body as a badge of honor and used it to express high social status in the tribe. Among the men, it symbolized strength and courage, and among the women it denoted the honoring of beauty and the rite of passage into adulthood.

There are numerous ancient and current cultures that would also fit in these categories with their own unique aspects, but for now these examples will serve as an overview. What follows is a journey back home, as I will take a closer look at my own country’s tattooing customs.

Thracians, Communism and the Mountains (Welcome to Bulgaria)

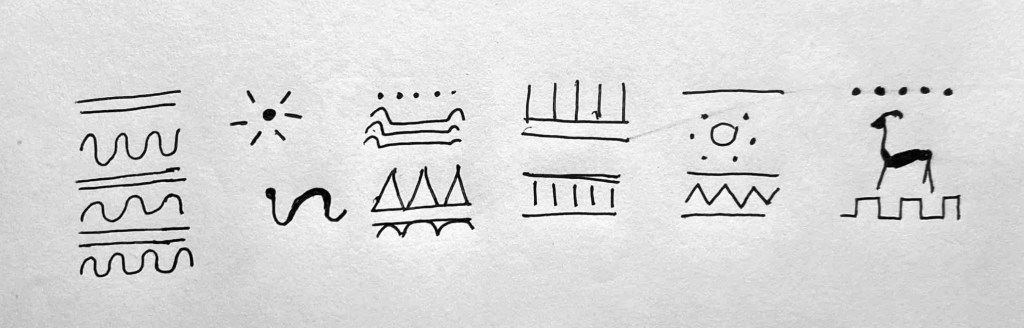

Bulgaria is an ancient country. One of the, if not the oldest continuously inhabited cities in Europe is Plovdiv, situated in south-central Bulgaria. We Bulgarians are proud of that heritage (България на три морета! Translated as “Bulgaria on three seas” – we like to use this statement to deflect from the fact that we are currently completely irrelevant, our past glory hidden within the pages of history books). Alongside our other ethnic ancestors, the Slavs and Bulgars, our land was populated by the Thracians, a collection of Indo-European tribes. They also populated parts of Northern Turkey and Greece. They were seen as barbarians by the other inhabitants and specifically, the Greeks, due to their fierceness as warriors and their more primitive appearance. The reason why I am bringing up the mighty Thracians is that they too had a tradition of tattooing, especially within the noble ranks. Tattoos for the men implied prowess in battle and success in conquest. A common motif were animals (such as snakes, deer and boars), that mirrored the wearer’s qualities in battle, as well as serving as their spiritual protectors. On the side of the women, tattoos were more decorative, but still held meaning, most commonly attached to family and fertility. I attempted to recreate some female Thracian designs that were exhibited in the Regional Historical Museum of Burgas:

The exhibition was called “Mirror of the past: female beauty through the ages” and the artworks were also recreated as temporary tattoos that visitors could purchase.

Let us now jump ahead in time, landing in Communist Bulgaria. The Communist regime began in 1946 and was dismantled in 1989. During that period, tattooing was frowned upon, as it represented individualism and rebellion. The three main domains of social life where tattoos were partially accepted were prison, the army, and on sea. In prisons, matches were used to engrave pigment on the skin, while sailors wore the typical anchor or compass. The biggest of these tattoo parlours was the army. Military training was mandatory, so all men who couldn’t or wouldn’t falsify their documents spent a year and a half of their youths contemplating a tattoo. What these spaces have in common is that they are isolated from the general public, so when the tattoo wearers had to join society again, they would largely hide their acquired tattoos with clothing. This effect of stigmatization of tattoos is felt nowadays with older generations, although not many are as repulsed by them as my grandmother!

Lastly, a community in the Bulgarian region, recognized for their tattoos are the Aromanian women from the Pirin and Rodopi mountains. They used to mark the spot between their eyes or their inner wrists with crosses, due to Orthodox Christianity being integral to their culture, and during the Ottoman rule of Bulgaria (14th to 19th century), to protect the young from getting kidnapped by the Turks. The Aromanians, among some other rural populations, were able to keep their strong Christian beliefs during the Communist period. My parents in their childhoods would sometimes encounter senior women with faded crosses on their foreheads in the Southwestern villages of Bulgaria, but the last generation of Aromanian women dedicated to this tradition has already passed.

Bulgaria has its own unique relationship to tattoos and I want my grandma to accept that tattooing is culturally important for us Bulgarians, even though we are so genetically mixed that none of us truly knows where we come from.

Worldwide Negative Connotations

Tracing our prejudices and challenging them is crucial to achieve a satisfying understanding of the world. In this section, we will take a peek at what events and practices form the negative connotation of tattooing some people discern.

Criminals were branded during the Han Period in China, Edo period in Japan and a plethora of other cultures, in order to distinguish them as dangerous, and as societal outcasts. Furthermore, Romans, Europeans and Americans in their colonial subjugations, branded their slaves. Branding and tattooing are two different practices – one uses a heated material (typically metal) in order to induce scar tissue and form raised skin, while the other etches ink under the middle layer of the skin. However, the outcome on surface level gives a similar impression and many nations practiced both methods side by side. Aboriginal Australians carved their skin in order to create raised scars in traditional patterns, which is more akin to a branding rather than a tattoo. Thus, branding and tattoos hold a similar ground in the collective consciousness, leading to a link between body modification and delinquency. In modern days tattoos are still associated with danger due to the prevalence of tattooing in prisons and organized crime groups. For instance, the members of the Yakuza, the notoriously violent mafia of Japan, use tattoos to separate themselves from the rest and to achieve an air of strength and authority. The tradition was converted from the branding of criminals in Japan to an expression of belonging to a subsection of people – the Yakuza in a sense took back their autonomy. That has led to many Japanese public bathhouses and beaches forbidding the display of tattoos, viewing it as an indicator of aggression.

Additionally, as mentioned earlier, there is a commandment in the Bible that condemns the practice of tattooing. Missionaries forbade traditional practices, due to their pagan origins in the name of religious conversion. With colonial powers (mostly Christian) spreading like ivy across the world, cultural traditions were extinguished or suppressed between the 16th and 20th century. For instance, the 16th century Spanish colonization of the Philippines had a significant impact on the indigenous tattooing culture, as the Spaniards imposed Catholic Christianity and European rigidity. In such suppressed communities, forced assimilation led to the loss of cultural knowledge. Some groups have managed to keep their traditions alive by word of mouth and concealed dedication to their culture. For example, the Maori tattooing tradition is still seen today due to the perseverance of the Maori people in spite of the British settlement of New Zealand. Representation in the public eye was achieved with public figures like Oriini Kaipara, a TV presenter of Maori descent.

Another outdated negative association we make with the art is the inclusion of tattooed people in “freak shows” around Europe in the 19th century. A famous tattooed duo from that time was the Howard siblings (Annie and Frank) and they were a regular attraction in P.T. Barnum’s infamous “Parade of Freaks.” They claimed that they were forcibly tattooed by natives after shipwrecking in the South Seas, while this couldn’t be further from the truth – they were tattooed by popular artists Martin Hildebrandt and Samuel O’Reilly. Hildebrandt had also tattooed his own daughter, who he saw as a great business opportunity. She was the first of the “Painted Ladies” and her forged story was that she had been tied to a tree and forcibly tattooed by Native Americans. This formula of made-up stories about violent indigenous tribes tattooing the poor and helpless European explorers was repeated numerous times for the entertainment of the masses. The fabrications surely fueled the European fear of the foreign and “exotic,” as well as the stigmatization of the tattoo.

All of these instances of negative representations have twisted the reception of the practice of tattooing as a threat, a sin and taboo. Tattoos, however, can also unite people, as we’ll discuss next.

Sociopolitical Statements and Artistic Expression

It is time to observe more recent conventions of tattooing, focusing mainly on Western Europe and the US, as they continuously set the bar for modern tattoo standards. During World War II there was a boom of patriotic tattoos among all sectors of the American army. Honolulu, Hawaii became the center of tattooing in the US and typical requests were “Remember Pearl Harbor” or “Hawaii 1944” and designs like a dagger through a rose, which symbolized the dedication of the soldiers. These tattoos united their wearers, who had a similar goal, similar traumatic experiences and similar sociopolitical views. A decline of patriotic tattoos would follow in the 60s and 70s, aligned with the appeal of the hippy movement formed in light of the Vietnam war. Women also started receiving more recognition as members of society and started solidifying their independence. For them, getting tattooed symbolized a newfound liberation, with tattoo artists at the time reporting that many of their female clients were going through divorces as they made the choice to etch art onto their skin.

Moving to the present, with the advent of social media, new trends would arise, uniting communities outside the digital realm. One such movement was the tattooing of Medusa artwork to symbolize empowerment and survival for sexual assault victims. The Ancient Greek myth of Medusa states that she was assaulted by Posseidon, the god of the ocean, in the temple of Athena. Athena then cursed Medusa, even though she was the victim of the violent act. While carrying a message in and of themselves, the tattoos also connect sexual assault survivors and create solidarity amongst them. A similar expression of strength and survival, but this time of sufferers of mental health issues is the semicolon, denoting continuous survival and perseverance through mental turmoil. The custom was started as suicide prevention, especially within teenagers – the semicolon is a pause in the sentence, not the end of it.

Finally I have to mention the artistry behind modern tattooing. There are countless styles and traditions in the tattooing world, from Old School (American Traditional) to Psychedelic or Bio Mechanic, there is something for everyone. Many experienced tattoo-getters underline the importance of working with an artist that you connect with and whose artwork grabs you, which is why extensive research and comparison should always be done before diving into the tattooing process. After all, you are entrusting them with your body and legacy. My personal favorite style of tattoos is Dotwork, as it creates a cloudy, flowy impression of the design when etched onto the skin. The beauty of tattooing is unveiled when a person combines their interests, cultural background, memories and aesthetic preferences in collaboration with a beloved tattooist to create art that will represent their identity.

New Hope

The way that scars, moles and eye color tell stories of accidents, sun exposure and genetics, tattoos tell the story of an individual’s inner and sociocultural life. Tattoos become a natural part of the wearer’s anatomy, a notion reinforced by the findings of mummies belonging to different nations, carrying their markings beyond death. So, what I’m saying is, I hope you now understand that this is bigger than both you and me, grandma (and please don’t reach for the rolling pin).

With love,

Ema.

Cover Photo:

Collectie Wereldmuseum (v/h Tropenmuseum), part of the National Museum of World Cultures, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

~ Dayak man, photographed in 1896

Sources:

Cloak & Dagger London. “Tattoos in the Spotlight: A History of Tattoos and Sideshows.” Cloak & Dagger London, http://www.cloakanddaggerlondon.co.uk/tattoos-in-the-spotlight-a-history-of-tattoos-and-sideshows.

Dimitrov, Ivan. “От Моряци До Баби.” vijmag.bg, 1 Apr. 2021, vijmag.bg/bg/article/moryatsi-babi.

Friedman, Renée, et al. “Natural Mummies From Predynastic Egypt Reveal the World’s Earliest Figural Tattoos.” Journal of Archaeological Science, vol. 92, Feb. 2018, pp. 116–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2018.02.002.

Gibbons, Bridget. “The Legacy of WWII Tattoos: Stories of Ink, Sacrifice, and Memory.” The National WWII Museum | New Orleans, 24 Mar. 2025, http://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/legacy-wwii-tattoos.

Goldstein, Norman. “Tattoos Defined.” Clinics in Dermatology, vol. 25, no. 4, July 2007, pp. 417–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2007.05.015.

Plath, Sylvia, and Ted Hughes. Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams: Short Stories, Prose, and Diary Excerpts. 1979.

Regional Historical Museum Burgas. “The Ancient Thracian Women Covered Their Arms and Legs With Tattoos.” Regional Historical Museum Burgas, 2017, http://www.burgasmuseums.bg/en/article/ancient-thracian-women-covered-their-arms-legs-tattoos-439.

Sayce, Paul. “Captain Cook Finds Tattooing in the South Sea’s.” Tattoo Club of Great Britain, 22 Nov. 2022, http://www.tattoo.co.uk/blog/post/tattoo-facts/captain-cook-finds-tattooing-in-the-south-seas?srsltid=AfmBOoqbqHnkG8-bX4cED8wVnj_HeqqLu5MHDApoUAtY7yo9iTiD0QGn.

Stoyanov, Slavyan. Когато Татуировките Бяха Спасение. istoryavshevici.blogspot.com/2019/12/blog-post.html.

Wanderlust Magazine. “History of Tattoos: Thracian Warriors Culture.” Wanderlust Magazine, 2 Aug. 2025, wanderlust-magazine.com/history-of-tattoos-thracian-warriors-culture.Yang, Anna. “Complete History of Tattoos – Illustrated Guide – TattoosWizard.” TattoosWizard, 23 Apr. 2024, tattooswizard.com/blog/timeline-of-tattoos-evolution.

Leave a comment