Growing up with a mother that has lived half of her years in Germany, I have always thought that I would eventually be able to speak that language. These past years, I have kind of managed to kick-start my German skills, but I still need to practise frequently. During the past weekend, I have actually struck up a conversation with two people from Germany. We talked mostly about our situation in life, what we studied and why we were in Amsterdam; so nothing really outstanding. However, something certainly stuck with me – though not because it was surprising. Both Germans were genuinely stupefied when I said that I liked their country, and looked at me funnily. The first one that I met even questioned “really?” repeatedly. One may suppose that they must not regard the places they come from in very high esteem, but I believe that, even if they did, they would have reacted as surprised as then.

Generation Z is all about acceptance, inclusion, respect. Us, young people, pride ourselves on our open-mindness, flexibility of character and general agreeable attitude towards everyone, whatever their condition, personality, race… At least, many media products speak on these terms. But this speech runs into a brick wall when it comes to opinion. From my own experience, the mask that gen Z puts on is the claim that everything is valid. You can be black or white, straight or gay, introverted or extroverted. Despite all that, “what do you mean you don’t like Blair from Gossip Girl? Don’t talk to me!”. Evidently, this kind of comments are done in the most nonchalant, humorous intention; and in an informal context as a general rule. Still, there are still a few manners in which these speakers could state that they like the character without making the other part feel uncomfortable, criticised, or invalid. Even if they do not get this sensation at all, the aggressiveness of the message is there. As a philology student, these kinds of pragmatic and semantic nuances of statements come across to me more clearly; although there is not much to uncover in “don’t talk to me”.

Not very shockingly, a satisfactory explanation to the increasing ruthlessness in voicing opinions could be found in social media. Generalised opinions grow at times from the lack of opinions at all, and/or the repetition from what is seen on TikTok or Instagram. The “valid” point of view is the one that has more likes, so it goes all the way from an impression to just a sectarian judgement, an agreement. I cannot opine that I like Germany, because I come from Spain, which is “the fun, nice country”, and Germans want to visit my country. It is not that they like one better, it just is like this. It cannot be the other way around, though I did not even say that I did not like my home place. More particularly, I also receive many weird looks when I say that I like rainy days and wintery weather, especially from the Spanish. Because sunlight is better. While biologically speaking, it might be; there is no real reason as to why one opinion is more socially accepted than the other one, apart from the majority factor. And that majority comes from the ghostly presence of supportive Internet people, who would surely agree with this girl that I happened to be talking to. But there is no one else participating in this exchange of words, there are no founded reasons or proof for any perspective; and now the conversation turns into a debate. In other words, a tangled succession of “what’s” and “how’s” is formed, and the part that has less virtual supporters loses.

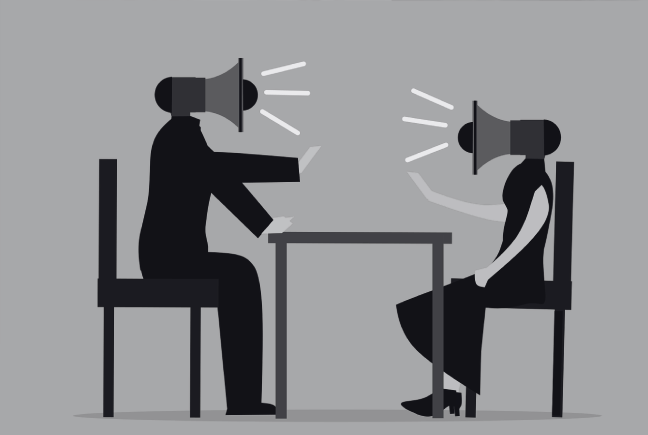

And this continues. There are a number of interactions on social media of the type of “I’m sorry, but this is better than that”, or “maturing is accepted that whatever is just >>>”. Which (apart from the exhausting repetitiveness of the platforms) derives into heated arguments online, then into real-life arguments, and now it seems that no one can just like or dislike something without having to make a statement about it. It gets tiring to have to advocate, with arguments and against all kinds of reactions, on the tiniest topics of all. People are preferring one month over another, not engaging in a (dialectical) war. Most of the time, what is being said is not that deep or relevant for one’s life. When there was no social media, we could only share and receive preferences of the people that surrounded us. Curiosity, discovery and interest were the base of hearing something new and striking. Currently, the power of popular opinion transcends to everything and everyone, so that it can only be one winner. For example, a very popular debate in Spain is whether the notebook that you had for primary school was red for Spanish and blue for Maths, or vice versa. Everyone is really invested in that discussion every time it pops up on X (formerly Twitter), and the yelling can almost be heard from the screen. When having a real conversation, the winner is the one that screams the most, or given the case, the majority “wins”. When talking about a hypothetical, ideal question, like whether there are more wheels or doors in the world; debating with friends can be real fun. It can be a hilarious, innocent way to spend a boring evening. But when simply saying things, what does it matter? What are we expecting to achieve? Is there going to be a supremacy of people liking Blair over Serena, a brutal victory of the red notebook over the blue one?

Nothing comes out of these brawls. At least, nothing positive, because there is for sure a lot of anger, discrimination, and selfishness in these kinds of assessments. It can be okay to be surprised by someone’s perspective, by the way in which they view the same world that we inhabit. Of course, it is always okay to disagree. But we cannot look for an ultimate superior dictum in matters of opinion, because there is none. Each to their own, or as the Spanish idiom goes, “to tastes, colours”. There are as many opinions, perspectives and sets of ideas as hues the human eye can see. So be okay with the tone of your skin, and be also okay with the shade of your classmate’s notebook.

Leave a comment