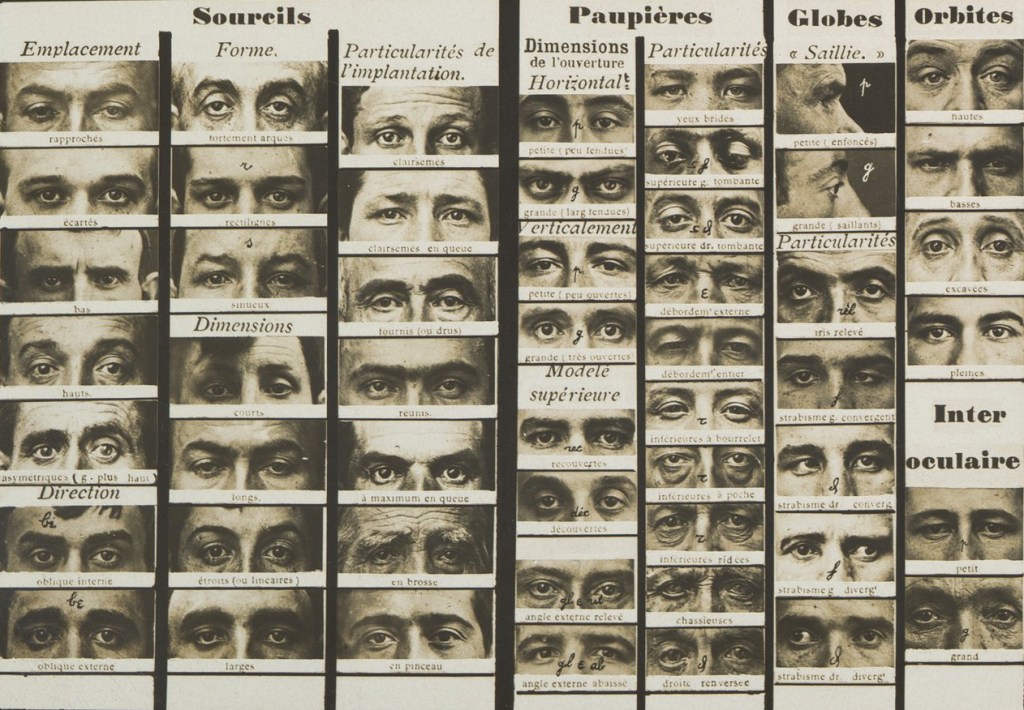

Synoptic Table of Physiognomic Traits: Eyes, Alphonse Bertillon

The current distrust of police is the culmination of a long history rather than a new development. Black Lives Matter has its roots in American civil rights and the abolition movement before it. The 1992 LA riots were a response to boundless oppression and generational trauma as much as to unpunished violence against a Black man, as have riots since. However, the ubiquity, or perhaps visibility of this distrust has seeped deeper into our collective consciousness than before. Warranted reexaminations of culture and its artifacts span wider and wider. Police procedurals are now scrutinized in this old but new light. The police procedural, the multi-media genre of ‘good detective enters new environment, investigates crime, solves crime, catches bad guy, leaves, repeat ad infinitum’, is such a cornerstone of media, a sort of eternal, unchanging presence, that analyzing it must feel like examining the complexities of a brick wall. It has been there forever, it has always been the same, and here it still is, brick on brick on brick like always. Still, the genre has rightfully come under fire in current and not-so-current progressive thought because the very bones of the genre are molded to quell suspicion and foster complacence towards police.

The TV/film/literary detective must be a good guy, while they may struggle with the occasional drinking problem or be colossally divorced, they cannot epitomize police brutality or the pervasive departmental complacency which allows misuse of law to fester and mawkishly blossom. The crime must be solved, the format demands a solution, it cannot become just another statistic to be filed away in the beigey bland police storage rooms that must hold untold mountains of unanswered grief. The criminal must be a bad guy, the catching and punishing of them must be satisfying for the viewer, and the genre leaves little room for examinations of systemic racism, extenuating circumstances, generational poverty and the lack of options these present. For the police procedural to be satisfying, engaging, and comfortable to watch, the genre demands an unproblematic hero, an unproblematically bad criminal, and an unproblematically solved case. The genre’s pillars and piles are all geared at creating a blind awe towards the police instead of a truthful portrayal. Many police procedurals have thus been coined ‘copaganda’. Unproblematic propaganda for the police. Of course, reality is problematic. Police can be corrupt and cruel, criminals can be desperate instead of malicious, or innocent altogether, and crimes go unsolved every day. The genre is not equipped to deal with this reality. However, some of these police stories are crafted by people that would like to deal with this reality nonetheless, people that would like to drag this maligned genre out of the infernal bowels, through purgatory, so that it may fight on the side of the angels once more.

In recent memory, there are two of these shows that come to mind, each with their own, flawed answer. Firstly, Law and Order SVU star Tracy ‘Ice-T’ Marrow recalls questioning the morality of his portrayal of a police officer in light of the rising public awareness of police brutality. The series’ showrunner Dick Wolf asked him whether he believed police were needed, to which he agreed. Dick then proposed Ice-T “play the cop that we need”. Ice-T concluded the interview by saying “if I play the cop that we need, I won’t have any problems with it”. On some level this is a kind and warm sentiment but it is not a solution. Police procedurals almost exclusively portray ‘the police we need’, giving the false cultural image that the police force is positively chock-full of virtuous, selfless white knights, and while a few of these surely exist, they cannot be as pervasive in reality as they are in television. Yet, this is exactly what the omnipresence of shows like Law and Order SVU suggest. Another television show that struggled with its own status as copaganda is Brooklyn 99. While progressive in nearly every aspect and touting many graceful treatments of sensitive topics such as sexism, homophobia, and mental health issues, after the killing of George Floyd one could feel the series squirm in the straightjacket of its own genre. In a fascinating feat of synchronicity, the show-writers sweated through the seams of the series as you saw the characters equally soak in the struggle. One the show’s central characters, Rosa, quit the force, stating that she could no longer justify working for the police. It was hard to read this as something other than the series’ writers declaring their own discomfort with still producing a show with heroic cops, flatly bad criminals, and cases with clear answers. Still, the show went on, with a heightened degree of self-awareness about its own nature, but it still laid brick on brick on brick till the old wall stood tall again. A valiant effort, yet self-awareness is a poor excuse for self-improvement.

A third option seems obvious: simply reject the genre. Modern films and shows like the disturbingly realistic We Own This City or the profoundly heart wrenching Queen and Slim reject every facet of the police procedural, no cleanly heroic cops, plainly evil criminals, and perfectly clean solutions survive the turn from genre to realism. These shows and films are deeply commendable, but the complete negation of genre across all police media would be a great loss. Genre is a useful thing. A thing humanity has worked very hard for. It provides a base of information, association, and feeling present in audiences any given creator may build on. Genre is a wealth of cultural heritage laboriously cultivated by thousands of books and films and shows all vaguely present in our collective consciousness. It creates comfort, accessibility, and immediate understanding for shows that aren’t particularly interested in breaking the mold, while granting shows that wish to surprise a standard to subvert, build upon, and alter. The argument that the flaws at the very base of the police procedural warrant its casting out into the depths forever is understandable, but I believe this would entail a profound loss.

There is a fourth solution, one that does not require willful ignorance, pointless self-awareness, or a complete rejection of the joys of genre. The genre needn’t struggle through purgatory or be cast under it forever, it can escape judgment completely, and enter a comfortably safe limbo, the space in the Christian doctrine for souls who were born of sin but had not the opportunity to repent. Like these souls, the police procedural is conceived irreversibly flawed: its base is built for propaganda, and it cannot correctly repent. However, it can exist outside of judgment, in limbo, through a shift in focus.

Ivan Sen’s 2023 Australian independent film Limbo performs this shift in focus superbly. Starring a brilliantly cast Simon Baker, most famous for his titular role in the police procedural The Mentalist, this film inhabits the structure of the police procedural faithfully and without shame: a flawed but ultimately virtuous detective arrives in a new location, is presented with an unproblematically evil crime, cleanly solves the crime and locates the unproblematically bad killer. It is a police procedural through and through. However, this adherence to genre is largely unimportant in the film, the crime occurred years ago and the killer dies of old age before being caught. What is actually essential to the film is the family that has been torn apart by this crime, by losing a child. Slowly, throughout the film, Baker’s detective helps the family broken by this crime meet, talk, mend, heal. When he drives out of town with the crime solved, the family sits together on their rusted outback porch closer together than they’ve been in years. The focus of the police procedural has shifted without ever leaving its genre or being uncomfortable with it. The police officer becomes more than the punisher of evil, he has become a shepherd and healer for those it affects. Limbo acts not only as a blueprint for how police procedurals can look but also how the police force itself could act.

The police procedural can keep its stringent rules and thrive, unashamed, within its confines. The format itself does not need to be changed. The shackles of genre countless creators have worked so hard to forge can be made crowns if the aim of the detective is changed, rather than the aim of the genre. We can keep the conventions and rules of our listlessly looping comfort-food cinema if its protagonists simply shift from seeking retributive justice, one based on avenging the victims and punishing the perpetrators, to striving for restorative justice, one based on restitution and healing. The function of police media is no longer to propagandize the police or villainize criminals, it has become an exploration of growth after pain and how we all might aid this process. It is a lesson our fictional and factual police have hardly begun to learn, but Limbo embodies it sensitively, gracefully, and completely.

Sources:

https://variety.com/2024/tv/news/ice-t-shuts-down-claim-law-and-order-svu-woke-1236120848/

Leave a comment